By

Ryan Fairall

One of the most important things a certified personal trainer can do is build out their new clients’ unique workout and training programs before diving in. These assessments help the trainer seek out opportunities for growth while also understanding their clients’ limitations at the moment.

Certified health and fitness professionals who want to effectively design individualized exercise programs for their clients, athletes, and possibly patients (with medical clearance), must first perform a detailed health and fitness assessment. These assessments often test the five most common components of health-related physical fitness: body composition, flexibility, muscular endurance, muscular strength, and cardiorespiratory endurance (American College of Sports Medicine, 2022).

However, other components have become much-needed additions to health and fitness assessments, such as muscular power (e.g., various jumps and throws), speed, agility, and quickness or SAQ (e.g., 40-yard dash, LEFT test, pro agility test, etc.), as well as various postural and movement assessments (e.g., static, transitional, and dynamic posture assessments).

One of the components of health and fitness assessments that has become increasingly popular over the last decade or so, has been the assessment of posture. Posture may be defined as “the relative disposition of the body parts in relation to the physical position, such as standing, lying down, and sitting” (National Academy of Sports Medicine, 2022a).

The assessment of posture utilizing these assessments and tests can be very subjective, specifically between certified health and fitness professionals, questioning the inter-rater reliability of some of these assessments and tests. One assessment that can sometimes be very subjective is that of static posture.

Performing a Static Postural Assessment

Health and fitness assessments commonly begin with collecting valuable subjective information from clients, athletes, and patients utilizing forms like the PAR-Q+ and the Lifestyle and Health History Questionnaire, as well as important objective measures, such as vital signs and body composition.

However, the next piece to the health and fitness assessment puzzle is often the assessment of posture, specifically static posture. Static posture may be defined as “the positioning of the musculoskeletal system while the body is motionless” (National Academy of Sports Medicine, 2022a).

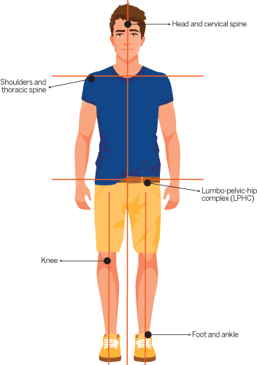

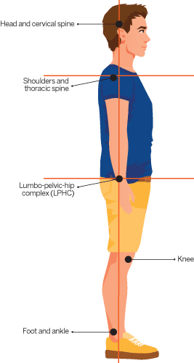

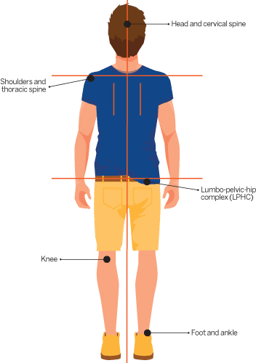

Static posture is commonly visually assessed in a relaxed standing position with no shoes, from an anterior, lateral, and posterior view (Figure 1). The five kinetic chain checkpoints (i.e., feet and ankles, knees, the lumbo-pelvic-hip complex or LPHC, shoulder complex, and the head and neck) are assessed from the three views, as the certified health and fitness professional attempts to witness any deviations from the optimal or ideal posture in the standing position.

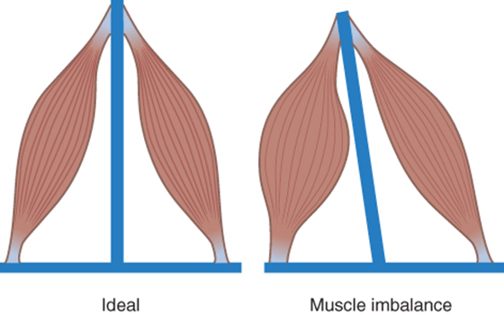

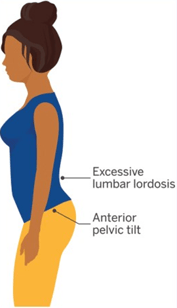

Three common postural distortion patterns that certified health and fitness professionals look for are pes planus distortion syndrome, lower crossed syndrome, and upper crossed syndrome (National Academy of Sports Medicine, 2022a). Any deviations from an optimal or ideal posture that may be witnessed could suggest the presence of possible muscular imbalances that may increase the risk of and eventually lead to both acute and chronic musculoskeletal conditions and pain for the client, athlete, or patient (Figure 2).

Figure 1. Static Postural Assessment (anterior, lateral, and posterior views)

Figure 2. Muscle imbalance

Visually Assessing Static Posture of the LPHC

The reason that the visual assessment of static posture may be considered subjective, and therefore possibly invalid, is that it can be very difficult for the certified health and fitness professional to detect possible postural deviations from what is optimal or ideal static standing posture. One of the areas of the static postural assessment that can be particularly difficult for certified health and fitness professionals to assess is the LPHC from the lateral view.

Attempting to visually assess the level of the anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS) in relation to the posterior superior iliac spine (PSIS), as well as the lumbar spine, may be difficult when clients, athletes, or patients are wearing loose-fitting clothing, or the certified health and fitness professional may not be well-versed in locating the ASIS and PSIS bony landmarks.

Even when the ASIS and PSIS bony landmarks are properly identified, visual assessment has shown poor inter-rater reliability among various healthcare professionals (i.e., chiropractors, physical therapists, physiatrists, rheumatologists, and orthopedic surgeons) (Fedorak et al., 2003).

This issue of invalid results may be significant considering postural deviations at the LPHC (e.g., lower-crossed syndrome) may lead to other postural deviations above (e.g., upper-crossed syndrome) and/or below (e.g., pes planus distortion syndrome) the LPHC and common acute and chronic musculoskeletal conditions, such as neck and upper back pain, shoulder pathologies, various knee pathologies, shin splints, Achilles tendinopathy, plantar fasciitis, etc.

What Is an “Ideal” Static Pelvic Posture? Is there one?

Neutral position while in a static standing posture is when the ASIS is in the same vertical line as the symphysis pubis (McKendall, et al., 2005). However, humans should naturally possess an anterior/lordotic curve and extension in the lumbar spine, but the curve should not be excessively beyond neutral position.

Within this posture, the ASIS may in fact be slightly inferior anteriorly when compared to the PSIS posteriorly, resulting in an anterior pelvic tilt. This has been demonstrated through multiple research studies showing various degree averages and ranges of an anterior pelvic tilt (as great as 27°) within normal asymptomatic individuals (Suits, 2021).

As seen in Figure 1 within the lateral view, when the ASIS and PSIS are level on the same horizontal line, the normal anterior/lordotic curve in the lumbar spine may be decreased, presenting an almost flat-back posture (i.e., the belt line being horizontal to the ground and the lumbar spine flattening).

When assessing static posture of the pelvis from the lateral view, the certified health and fitness professional is checking if the pelvis is in a neutral position, anteriorly tilted, or posteriorly tilted. As previously stated, according to McKendall, et al. (2005), the pelvis is in a neutral position when the ASIS is in the same vertical line as the symphysis pubis.

The pelvis is in an anterior pelvic tilt if the ASIS is anterior to the symphysis pubis and posteriorly tilted if the ASIS is posterior to the symphysis pubis (McKendall, et al., 2005). Considering that it can be easily viewed as more difficult to assess the ASIS and the symphysis pubis along a vertical line, as opposed to the ASIS and PSIS along a horizontal line, what are certified health and fitness professionals to do when attempting to assess the LPHC and determine pelvic posture?

Trusting the Entire Assessment Process

First, it is important that certified health and fitness professionals understand from the research that normal asymptomatic individuals may very likely present an anterior pelvic tilt, even when using the measurement of the ASIS and PSIS along a horizontal line to determine pelvic posture (Suits, 2021).

Secondly, when assessing static posture, certified health and fitness professionals must look for obvious deviations from the optimal or ideal static posture. For example, an exaggerated anterior pelvic tilt, excessive lumbar lordosis, and flexed hip joints, as with lower crossed syndrome (Figure 3).

When certified health and fitness professionals attempt to look so closely to determine if there are any static postural deviations, they are much more likely to find something, even if the deviations are in fact insignificant. Therefore, lastly, it is essential that the certified health and fitness professional look at the static postural assessment as simply a teaser for the rest of the assessment process.

Figure 3. Lower Crossed Syndrome

The certified health and fitness professional must allow the results of subsequent parts of the assessment, such as the overhead squat assessment, single-leg squat assessment, pushing, pulling, and pressing assessments, and mobility assessments, such as those covered within NASM’s Corrective Exercise Specialization (CES), to verify the presence of possible muscular imbalances that may have been suspected while performing the static postural assessment.

If there are any possible muscular imbalances associated with static postural deviations (e.g., an excessive anterior pelvic tilt and lumbar lordosis), the certified health and fitness professional must feel confident that these deviations will become much more apparent when the client, athlete, or patient performs subsequent assessments.

References:

American College of Sports Medicine. (2022). ACSM’s fitness assessment manual. (Y. Feito & M. Magal, Eds.) (6th ed.). Wolters Kluwer.

Fedorak, C., Ashworth, N., Marshall, J., & Paull, H. (2003). Reliability of the visual assessment of cervical and lumbar lordosis: How good are we? Spine, 28(16), 1857–1859.

Kendall, F. P. (2005). Muscles: Testing and function with posture and pain (5th ed.). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

National Academy of Sports Medicine. (2022a). NASM essentials of personal fitness training. (B. G. Sutton, Ed.) (7th ed.). Jones & Bartlett Learning.

National Academy of Sports Medicine. (2022b). Nasm essentials of corrective exercise training. (R. Fahmy, Ed.) (Second). Jones & Bartlett Learning.

Suits, W. H. (2021). Clinical measures of pelvic tilt in physical therapy. International Journal of Sports Physical Therapy, 16(5), 1366–1375.