Training modifications and exercise programming for older adults are popular topics across health and fitness publications and conferences. There’s good reason for this: By 2050, the number of people 60 or older will increase to 2 billion, up from just 900 million in 2015. Put another way, in 30 short years from now, nearly a quarter of the earth’s population will be over age 60 (WHO 2018). That adds up to a lot of potential members, clients and group fitness participants!

Many fitness professionals already gravitate to older populations because they are gratifying to work with. Given the right exercise programming, these clients can experience important increases in functional capacity and health—categories many trainers deem to be more impactful than aesthetics and sports performance.

This article originally appeared in the Spring 2020 Issue of American Fitness Magazine.

NO ONE-SIZE-FITS-ALL APPROACH TO TRAINING OLDER CLIENTS

Too often we are told which exercises or training variables are “appropriate for older clients. There are a couple of unintended consequences here: First, it suggests that many of the exercises we know and love are not appropriate for older clients. Second, it implies that older clients are, by default, limited in some way. Of course, neither is accurate.

So, how should programming for older adults differ from our usual approach? The short answer: At its foundation, it shouldn’t have to. Great fitness professionals excel at meeting clients where they are—regardless of chronological age—and working with them to improve lifestyle and functional capacity in accordance with health and fitness goals. This means shifting our mindset from “age-based” program design to “capacity-based” programming. Though this sounds like a fairly simple change, it’s important to understand why it matters—and how it applies to those we serve.

A DEFINITION OF HEALTHY AGING

According to the World Health Organization’s 2015 World Report on Ageing and Health, healthy aging is “the process of developing and maintaining the functional ability that enables well-being at an older age.”

Our goal as fitness and wellness professionals should be to assist our clients in maximizing their functional ability, or “the health-related attributes that enable people to be and do what they have reason to value” (WHO 2015). This process must be individualized to each client.

WHAT IS FUNCTIONAL ABILITY?

Functional ability is a result of the complex interaction between a person’s environment and his or her intrinsic capacities. Intrinsic capacities include all of the person’s mental and physical capacities, including genetics, a predisposition to or presence of disease, and various lifestyle factors (WHO 2015). Environment includes everything in the individual’s external world, including living space, local community resources and society at large. As a fitness provider or facility, you are part of a client’s environment.

PHYSICAL CAPACITY AS IT RELATES TO TRAINING OLDER ADULTS

Physical capacity is the body’s ability to perform specific tasks. This is the component of intrinsic capacity that is most influenced by exercise and, therefore, by the work of fitness professionals. Physical capacity should not be thought of as something that “automatically” declines with age but, rather, as something that falls within a range that typically widens as we get older.

In actuality, some people experience a decline in physical capacity earlier in life, owing to the interplay of environment and intrinsic capacities, so there are people in their 70s who have the physical capacities of individuals in their 20s.

ABILITY AND NATURE VERSUS NURTURE

Staying healthier and maintaining our functional ability as we age is neither random nor due to a genetic lottery. More relevant is whether our physical and social environments offer us opportunities to adopt a healthy lifestyle and give us access to adequate health care, programs and services.

Some researchers suggest that genetics are responsible for only 25%–40% of healthy aging (NIA n.d.). This means the remaining 60%–75% comes from lifestyle and environmental factors. Given the wide health range among older populations, combined with the relatively minor impact of genetics, it is easy to see why designing a program for an older client is a completely individualized process.

EXERCISE PROGRESSION AND FUNCTIONAL CAPACITY FOR OLDER ADULTS

With any of our clients, we work to understand their baseline fitness level and abilities, then we combine this knowledge with their needs and goals to create a tailored exercise program. The program is then systematically progressed (i.e., the challenge level is adjusted) to maximize results.

It’s essentially no different with an older client. The two things to keep in mind are (1) as always, we must not assume anything about a client’s ability prior to completing the intake and assessment steps, and (2) exercise variable selection may need to be more creative than it would for a younger person.

FITNESS ASSESSMENTS

The general approach of the NASM Optimum Performance Training™ model can be applied to any population; however, different client groups do face unique challenges. Older adults generally experience a number of physical changes, and exercise programming may need to take these into account.

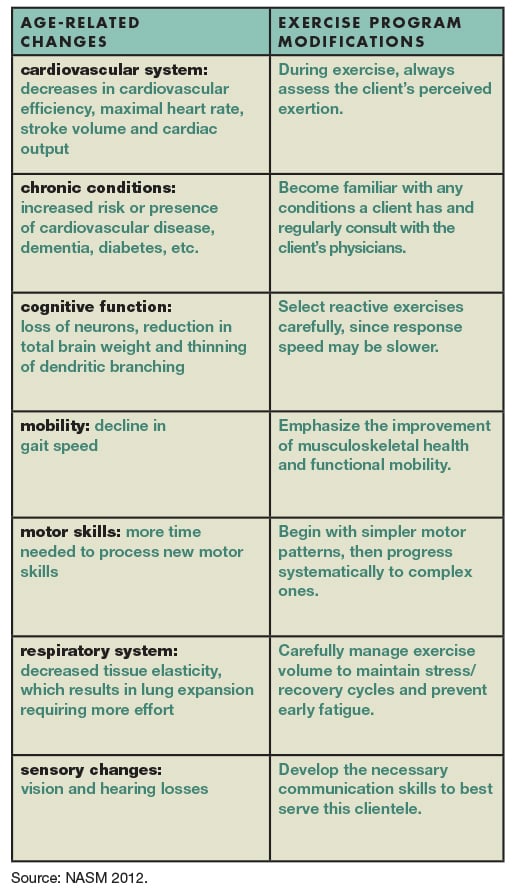

They include reductions in muscle mass and bone mineral density, a loss of elasticity in connective tissue, and a decline in balance and coordination skills. Compared with earlier in life, maximal heart rate and cardiac output may also be lower among older clients, while blood pressure will tend to be higher, both at rest and during workouts (NASM 2018). As with clients at any age, there may also be health conditions, medications and previous injuries that affect exercise ability and performance. (“Age-Related Changes—and How to Accommodate Them,” below, offers tips for addressing some of the most common.)

To be sure you have all of the information you need to keep your older clients safe, have them complete the Physical Activity Readiness Questionnaire (PAR-Q) as part of their intake. This can help you decide whether you want them to provide a doctor’s clearance before they begin working with you (NASM 2018).

ESTABLISH A BASELINE WITH ASSESSMENTS

Movement assessments, such as the overhead squat, single-leg balance, push, pull and sit-to-stand (from a chair), are a great place to start (NASM 2018). More advanced assessments, like those found in the NASM Essentials of Corrective Exercise Training manual, are also appropriate. For example, the treadmill walking (gait) assessment and the upper-extremity transitional assessments will provide a snapshot of clients’ starting mobility and neuromuscular control (NASM 2014).

Other tests can be adapted for this group, too, keeping in mind age-related reductions in muscle mass and cardiac output. Instead of a one-repetition maximum strength test, for example, you can do a 10-RM, and cardiorespiratory fitness can be measured with the “talk test.” Assessments should be selected and modified to suit client goals and abilities.

GET CREATIVE WITH EXERCISE PROGRESSION/REGRESSION

Proper exercise progression and regression is one of the most essential skills that fitness professionals must master. Good exercise progression goes beyond simply selecting different exercises. It involves purposefully and systematically creating a stimulus that is just challenging enough to force the kinetic chain (aka human movement system) to improve in order to adapt to the stimulus. Not challenging enough, and the kinetic chain may not respond as desired.

Too challenging, and the kinetic chain will struggle to execute the exercise well—the system may be overwhelmed and not recover properly. For all moves, the intensity should be appropriate to the client’s goals and abilities, though the basic guideline for seniors is 40%–85% of VO2peak (NASM 2018).

Strength, mobility and the ability to move quickly are all important qualities for older clients to develop, so don’t shy away from appropriate resistance training; flexibility exercises; power training; and speed, agility and quickness (SAQ) training. Below are details on a few of these.

HOW TO DO RESISTANCE TRAINING FOR OLDER ADULTS

With older adults, as with any other clients, resistance training should follow the principles of the NASM OPT™ model: Individualize, progress and schedule strength training, beginning with Phase 1: Stabilization Endurance. What is often overlooked with older populations is the importance of developing muscle growth (hypertrophy) and power (Phases 4 and 5).

Even with age-related declines in muscle tissue, older exercisers who participate in long-term resistance training can preserve strength, power, and muscle mass and function (NASM 2012). Moreover, clients with compromised neuromuscular control, marked mobility limitations or frailty can still benefit from resistance training when it is properly applied. (See “What Is Frailty—and Can Exercise Cure It?,” below, for more on this condition.)

When coaching older clients, remember that it is critical for them to be able to maintain precise technique and kinetic chain control at all times to minimize risk of injury, so be sure to apply regressions as needed to make that happen (NASM 2018). On the other hand, don’t stop your 80-year-old clients from deadlifting for eight repetitions if that’s safe, if they qualify for it, and if it’s appropriate to their goals.

SAQ AND PLYOMETRIC TRAINING

Integrated training components that are often underutilized with older adults include SAQ and plyometric training, and yet improving the ability to move with explosiveness, quickness and efficiency can benefit everyone—especially older clients experiencing mobility issues.

Too often, when trainers imagine SAQ for an older adult, they picture aggressive cone or ladder drills that they fear may lead to injury, so they omit this type of training. Other fitness professionals are so afraid to “break” their clients that agility training becomes too simplistic to produce real improvement. The bottom line is that ladder drills, simple step patterns and everything in between are great if they are appropriately selected, individualized and applied. The same is true for plyometric training.

Remember: Progressions for older adults require us to be creative. If we understand the purpose behind a particular mode of training, we can create programs at many challenge levels—and thereby meet any client’s needs.

CONCLUSION: THE ROLE OF THE FITNESS PROFESSIONAL

The key takeaways here: Chronological age is not a measure of physical or functional capacity. Though we should be aware of common age-related declines in physiological function, we must remember that there is no such thing as a “typical” older person, so we should approach all clients with the mindset of assess, not assume.

In sum, when working with an older adult—as with any client—you need to ask yourself: Does this particular individual have the capacity to do what he or she wishes to do within the current set of circumstances and opportunities? And if not, what can we do about it?

BONUS CONTENT: WHAT IS FRAILTY—AND CAN EXERCISE CURE IT?

Frailty is an umbrella term encompassing the overall impairment of a biological system’s ability to respond to stressors. When trainers first begin working with older clientele, they often assume frailty right from the start. However, frailty affects only about 15% of U.S. adults over age 65, so the majority of your older clients will not be in a state of frailty (Bandeen-Roche et al. 2015).

Frailty often results from the convergence of aging, lifestyle and chronic disease. Declining physical activity and losses of muscle mass and musculoskeletal function are risk factors for frailty. Interestingly, frailty has also been found to be heritable, and genetic influences on frailty increase with age (Steves, Spector & Jackson 2012).

The underlying good news here is that muscle mass and function are trainable, so while exercise doesn’t “cure” frailty, its muscle-related aspects can be improved, at the very least. Resistance training is often well-accepted by frail populations and is shown to be beneficial to their physical capacity (Lopez et al. 2018).

AGE-RELATED CHANGES—AND HOW TO ACCOMMODATE THEM

When training older clients, it is more likely that some accommodations will be necessary due to the greater prevalence of health conditions, preexisting injuries and other factors. However, the rate at which different physiological systems experience change or decline will be unique to each individual (Steves, Spector & Jackson 2012). An older client may experience none or all of the age-related changes listed below; thus, a thorough client intake is necessary to create a unique health and wellness baseline.

The table gives accommodations that can be used to address common age-related changes, many of which are discussed in depth in the NASM Senior Fitness Specialist Manual.

SAMPLE ASSESSMENT: SAQ AND THE TUG TEST

(With Progressions/Regressions)

Let’s consider a common example of a speed, agility and quickness (SAQ) exercise progression for clients with mobility limitations and/or slowed gait speed. In research, gait speed is often used as a measure of functional capacity and seen as an indicator of overall musculoskeletal health in older age (WHO 2015).

Gait speed is the time required for an individual to walk a predetermined distance (often 4 meters, or 13.12 feet) using their usual (habitual) gait. It can also be evaluated during a multicomponent task that mimics important activities of daily living. A simple place to start is with variations of timed-up-and-go (TUG) tasks used in research (Cadore et al. 2014).

The TUG Test. In its most basic application, clients are timed as they rise from a chair, walk 3 meters (about 10 feet), turn around, walk back to the same chair, and sit down again.

Regression of the TUG Test. For a client with advanced mobility limitations, a TUG task can be regressed to standing from the chair with assistance, taking 1 or 2 steps, then returning to the seated position with assistance. Another example: Clients with somewhat greater balance and mobility can stand and sit without assistance and walk for 1 meter instead of 3.

Progression of the TUG Test. There are many options for this, including increasing travel distance or gait speed, using patterns such as side steps or shuffles, and having clients navigate obstacles. At an advanced level, an isometric squat position can replace the “seated” position, and the “go” portion can incorporate complex patterns, sprinting and/or explosive movements.

As you see, the TUG Test can be the basis of a multitude of SAQ progressions for older clients, ranging from those who are frail all the way to advanced athletes. Again, the important thing is to base progressions on the client’s capacity, not on age.

Great fitness professionals excel at meeting clients where they are—regardless of chronological age—and working with them to improve lifestyle and functional capacity in accordance with health and fitness goals.

Strength, mobility and the ability to move quickly are all important qualities for older clients to develop, so don’t shy away from appropriate resistance training; flexibility exercises; power training; and speed, agility and quickness (SAQ) training.

Progressions for older adults require us to be creative. If we understand the purpose behind a particular mode of training, we can create programs at many challenge levels—and thereby meet any client’s needs.

REFERENCES

Bandeen-Roche, K., et al. 2015. Frailty in older adults: A nationally representative profile in the United States. The Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, 70 (11), 1427–34.

Cadore, E.L., et al. 2014. Multicomponent exercises including muscle power training

enhance muscle mass, power output, and functional outcomes in institutionalized frail nonagenarians. Age (Dordrecht, Netherlands), 36 (2), 773–85.

Lopez, P., et al. 2018. Benefits of resistance training in physically frail elderly: A systematic review. Aging Clinical and Experimental Research, 30 (8), 889–99.

NASM (National Academy of Sports Medicine). 2012. Senior Fitness Specialist Manual. Leawood, KS: Assessment Technologies Institute.

NASM. 2014. NASM Essentials of Corrective Exercise Training(Revised ed.). Burlington, MA: Jones & Bartlett.

NASM. 2018. NASM Essentials of Personal Fitness Training (6th ed.). Burlington, MA: Jones & Bartlett.

NIA (National Institute on Aging). n.d. Our genes are key to how we age. Accessed Apr. 1, 2020: nia.nih.gov/about/living-long-well-21st-century-strategic-directions-research-aging/our-genes-are-key-how-we.

Steves, C.J., Spector, T.D., & Jackson, S.H.D. 2012. Ageing, genes, environment and epigenetics: What twin studies tell us now, and in the future. Age and Ageing, 41 (5), 581–86.

WHO (World Health Organization). 2015. World Report on Ageing and Health. Accessed Mar. 30, 2020: apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/186463/9789240694811_eng.pdf?sequence=1.

WHO. 2018. Ageing and health. Accessed Apr. 1, 2020: who.int/news-room/facts-