What can you do when you have serious health and fitness goals…but you just don’t like vegetables? First, know that you’re not crazy (and you’re not alone). Next, try our 3-step formula to go from spitting out to seeking out the veggies you used to hate.

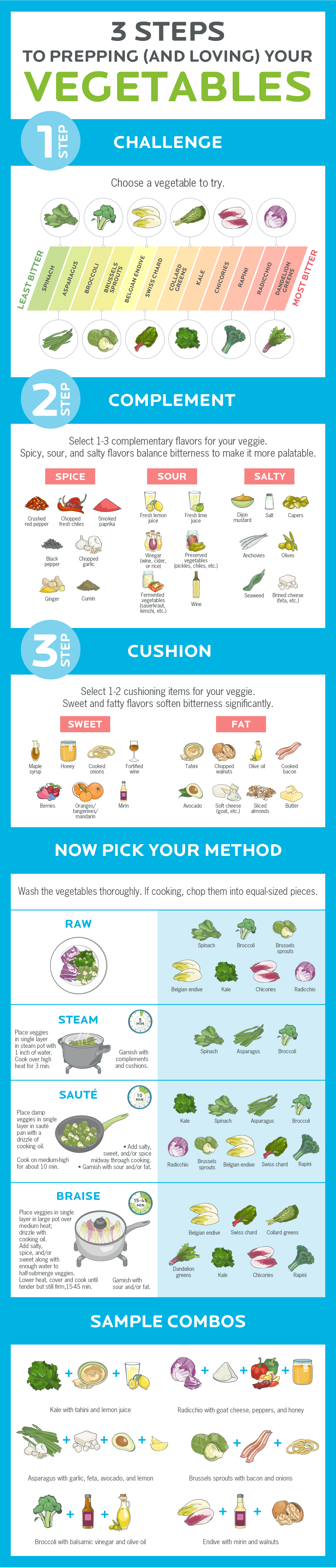

- We also created a cool visual guide. Check out the infographic here…

++++

Whether Paleo or vegan, fasting or “feed-often”, Mediterranean or New Nordic, almost all “health-conscious diets” agree on one thing:

You should eat your vegetables.

“Eat your veggies” is a childhood mantra, a government agency slogan, and a lesson that almost any health or fitness coach will eventually teach their clients.

Even newbies know they should be “eating the rainbow” (though they don’t always know how).

But many of our clients don’t like vegetables.

In fact, they HATE them, because many vegetables are bitter.

Personally, we like broccoli. We could happily eat bags of the stuff.

And spinach, and carrots, and radicchio, and arugula (rocket), watercress, Brussels sprouts, and any other plant that makes many people squinch up their faces and say Euw.

We love them all.

However, many vegetables have chemical compounds that make them taste bitter to some people. And, quite reasonably:

Many people avoid bitter things.

To them:

- Broccoli = stinky socks.

- Green peppers = turpentine.

- Escarole = Little boats of bitterness floating on your tongue’s tears.

Now we have a dilemma.

- Vegetables are good and healthy, and important.

- Everyone’s taste preferences are different.

- Some people may be genetically more likely to dislike vegetables.

- How do we get the benefits of vegetables if we don’t want to eat them?

So, in this article, we’ll explain:

- Why some people don’t like vegetables.

- Why they’re not bad or wrong for disliking vegetables.

- What to do about this.

Yes, vegetables are good.

- Vegetables are full of nutrients that your body loves. Vegetables are bursting with antioxidants, vitamins, minerals, fiber, and phytonutrients. These nutrients help keep you healthy and avoid deficiencies (which make you feel really bad).

- Vegetables have a lot of volume, but not a lot of calories. So, they fill up your stomach without adding a lot of extra calories. This can help you control energy balance (calories in vs calories out), and help you maintain a healthy body weight, or lose body fat without feeling too hungry.

- Vegetables add fiber. Fiber not only helps us feel full, it feeds our intestinal bacteria, helps push things through our digestive tract, and helps to excrete unwanted waste products.

- Vegetables add water. Staying hydrated is good. The extra water also helps the fiber do its job.

- Vegetables add variety. With so many different kinds of veggies to try, learning to enjoy them can help you stick to healthy eating.

Of course, in theory, you could eat “too many vegetables”… but for most people, that would mean eating several pounds a day. (And lots of bathroom unpleasantness).

Most people, of course, have the opposite problem: barely eating any vegetables at all.

Despite the benefits of vegetables:

Veggie-phobia is coded into our DNA.

Undoubtedly, you’ve heard of the “four flavors”: salt, sweet, sour, and bitter.

In recent years, four more flavors have been identified:

- fattiness

- spice/heat

- umami (referring to a savory “meatiness”), and

- kokumi (a mouthfeel that might be described as “heartiness”).

For most people — especially veggie-phobes — bitterness is plants’ dominant flavor.

Yet vegetables can also verge on sweet (think carrots, peas, corn, roasted beets, winter squash, or obviously sweet potatoes) or astringent (legumes, celery, Brussels sprouts, parsnips).

Bitterness comes from alkaloids.

These are nitrogen-based chemical compounds that plants, fungi, and bacteria make to defend themselves against attacks from things like parasites, pathogens, and animals that might eat them.

Alkaloids are a big group of chemicals and have all kinds of different effects. They can be:

- deadly (like the atropine in deadly nightshade),

- psychotropic (like psilocybin in psychedelic mushrooms),

- painkilling (morphine, codeine),

- antimalarial (quinine), or

- stimulating (hooray for caffeine!).

So alkaloids, as a group, have many uses.

But since they can be so dangerous, we’ve evolved to quickly and easily detect (and spit out) their trademark bitterness.

And modern humans aren’t the only ones fighting their parents over broccoli. Rats will reject bitter foods even if you cut the link between their brainstem and cortex, indicating that other species reject bitterness too.

Not liking bitterness might be more like an innate reflex (in other words, something you can’t really control) than a preference.

So when your clients (or your kids) tell you they can’t stand the taste of kale, your response can start with, “That makes perfect sense.”

Why are some people okay with bitterness while others aren’t?

We’ve known for almost 100 years that people vary quite a lot in how much they can detect and tolerate different bitter tastes.

Flavor is complicated.

Our palate, which is our appreciation for complex combinations of tastes, is determined by three factors.

Factor 1:

What flavors are we exposed to in the womb?

Have you ever seen a child eat food that was too hot for you? I have, in rural Thailand.

The lady I was eating with explained: “Farang should not eat the yellow chilies”. Naturally, this farang [basically, white guy] — being young and stupid — paid no attention to this warning whatsoever.

I think this was the first time that food hurt me.

What concerned my young ego, even more, was watching a boy of about 6 eat the same dish as me without apparent concern (or having to drink four beers to kill the heat).

Now, this isn’t just a matter of practice.

Flavor preferences are actually passed on before birth. Amniotic fluid contains a remarkable array of biological scent molecules, and children get exposed to flavors before they can even eat.

(Fun fact: The first research on this was weird — they fed pregnant mothers garlic capsules and then had volunteers smell their amniotic fluid!)

Factor 2:

What’s our genetic makeup?

Much of the modern work in the genetic basis of taste starts with a substance called PROP (6-n-propylthiouracil). Some people, it seems, find this substance overwhelmingly bitter.

Others literally can’t taste it. At all.

Being a non-taster isn’t a problem. I’m a “non-taster” myself. We’re the “normal” ones, actually.

Overall, “PROP tasters”, who make up about a quarter of people, are the ones with the problem because a lot of food tastes bad to them. They’re really, really sensitive to most strong flavors. This includes sweet, hot… and, you guessed it, bitter.

It’s easy enough to tell if you’re a supertaster. Do you like hoppy beers, grapefruit juice, kale, tonic water, espresso, and/or Sicilian olives? If so, you are not a supertaster.

If you find these flavors overwhelmingly strong, then it’s likely you’ve got sensitive buds.

Factor 3:

What have we learned and practiced?

Of the three factors, conditioning, familiarity, and practice are probably most important. Our palates can get used to flavors when we taste them over and over again.

Few people like the way coffee taste the first time, for example. Beer usually really splits the room the first time as well.

But since we all enjoy the buzz, the flavors of beer and coffee become more accessible. Eventually, we just love the bitter flavor.

Here are some ways we may learn about our taste preferences:

How were we raised?

Some people grew up on TV dinners and were simply not exposed to vegetables growing up.

Some people were exposed… but badly! Have you ever had boiled cabbage or microwaved Brussels sprouts? If you have, I am sorry.

On behalf of vaguely Anglo-Saxon people everywhere, I formally apologize for the stunningly awful things my people have done to vegetables.

Over-steamed limp beans, soapy carrots, gray peas… we’ve all had them. And some poor people had them every day.

What’s our culture?

Where did you grow up? What did your family do? What’s your heritage?

Tastes, texture, and odors change wildly between geographic, cultural and ethnic groups.

This part isn’t genetic. It’s simply what you grow up believing is normal, what you’re taught to appreciate and, for large chunks of human history, what stood between you and starvation.

If you’ve been to the markets in Hong Kong, you might be familiar with the assault on your senses that is stinky tofu.

This is one of the few foods I could never bring myself to try. I didn’t even want to stand near it. It’s amazingly unpleasant… unless you grew up with it, of course. In that case, it’s probably amazing.

Naturally, this goes for bitter flavors as well.

If you grow up eating bitter melon, as people do in South and East Asia, I’m willing to bet you find other bitter flavors less overwhelming.

If you grow up with the scent of cabbage, neeps (turnips), and onions in an Eastern European, Scottish or Irish home, you might find these tastes comforting.

Do you eat whole or processed foods?

In the modern iceberg-and-watery-tomato-in-a-salad world, bitter foods aren’t common either.

If your intake is more packaged food, less fresh food, then your palate will be that much more conditioned to prefer and seek out the fatty, sweet flavors that processed food has to offer.

Modern agriculture has significantly affected our tastes.

Most modern plants and animals have been carefully selected not for flavor, nor texture, but for yield and attractiveness.

This means big chickens that grow fast. Wheat that grows short and fat and speedy. Tomatoes that stay firm and bright red (even if they happen to taste like styrofoam).

Unfortunately, modern agriculture has little interest in making things taste good.

Many foods have had their natural, complex, intrinsic flavors stripped away, simply because preserving the richness of flavor wasn’t the main goal.

Food companies are in the business of selling the most food to the most people.

This means they’re looking for flavors that are:

- very satisfying; and

- very accessible.

That rules out sharp flavors, fresh flavors, organic flavors, astringent flavors, “kinda grows on you” flavors, and so on.

How you perceive the taste of veggies affects your fitness and health.

If we know what flavors you like and prefer, we might actually be able to predict your body composition or your health.

Yes, people vary by age, country, and culture (for instance, German kids like fat the most, Spanish kids like umami the most).

But overall, if you like sweet and fatty flavors a lot, there’s also a chance that you might have a higher body weight; the reverse is true as well.

We don’t know for sure if taste preference changes body weight or whether body weight changes taste preference.

But what we do know is:

We can change our flavor preferences.

While you might think you’re an adult, and your palate is “set”, research suggests that taste preferences/drives can change a lot over time.

In other words, if you hate bitter flavors, you can change that… if you want.

3 steps to really love your veggies

Regardless of where you’re starting — never eaten a green thing ever, or just want some new ways to eat plants — there is a simple formula you can use to make bitterness less intense, more palatable, and much more enjoyable:

- Challenge.

- Complement.

- Cushion.

1. Challenge.

Find a bitter food, something that requires a special effort, and something that you won’t normally just eat.

Psych yourself up. Put on your ragiest, peppiest music as a soundtrack. Do a primal scream.

You’re going to TASTE that kale! YEAHHHHHHH!!! BITTER BEAST MODE!!!

Then…

Do it.

See what happens.

You may hate it… you may love it… you may just think “meh”.

Either way… you have now been brave, and at least tried it.

Research suggests that we may need to try new foods many times before we’ll tolerate or like them. So, challenge yourself regularly. You might be surprised about what happens.

2. Complement.

Building on the complexity of flavor perception, almost all well-developed recipes use a kind of “flavor harmony”.

In this case, it means pairing a food or aromatic with your vegetable to push several taste/flavor buttons at the same time.

We can actually predict some of this harmony in advance now, using complicated measurements like gas chromatography. But generally, we rely on chefs — who often have an amazing intuition about “what goes with what” — to do it for us.

3. Cushion.

Pairing bitterness with certain flavors can magically turn its volume down.

How?

On your tongue, you have a variety of receptors that bind to the chemicals in food. When these receptors get a chemical signal, they send information to the brain about what you are “tasting”.

(Variations in the number and type of these receptors help give us our innate flavor preferences.)

Chemical signals are like cars on a roadway. Sometimes the road to the brain is clear, sometimes the road can get jammed.

Sweet and fatty flavors, in particular, can jam up the road and interfere with our brain’s perception of bitterness. Even the specific types of sugar and fat can matter (for instance, butter versus olive oil; glucose versus fructose, etc.)

So, after we have chosen our Challenge food and a Complement, we find a Cushion.

Excellent Cushions for bitterness include honey, maple syrup, oil, almonds, and butter.

Don’t freak out if those sound calorie-dense. We just need balance, not a cup of oil or a pound of bacon.

Now, check out the matrix below.

- Pick one challenge.

- Pick one compliment.

- Pick one cushion.

Pay attention to the simple cooking methods, which help you preserve the vegetables’ texture (mush ends here, people.)

As you become more comfortable, experiment with combining more flavors — up to one item per category. The different combinations are endless.

What to do next:

Some tips from Precision Nutrition

At PN, we like the mantra, “Progress, not perfection.”

Do what works for you right now… and at the same time, be open to change in the future:

1. Forget about “rules”.

Pay no attention to people who insist that all vegetables should be “cold pressed” or “eaten natural” or “bathed in cosmic vibrations” or whatever else is necessary to “preserve their essential properties”.

This is silly. Cooking and seasoning is a thing. Thousands of years of human cuisine exist for a reason: To make foods digestible and taste good.

Newsflash: If “preserving the essential health properties” of something means it tastes like lawn clippings, it doesn’t matter! If you won’t eat it…

It.

Is.

Not.

“Healthy”.

2. Try a new colorful vegetable.

Go and cruise the aisles of your local grocery store or farmer’s market.

Ask other people what they like. (I’ve had conversations in my produce aisle with people who are curious to try stuff.)

Look for the less-bitter options to start, like:

- cherry tomatoes

- butternut or other winter squashes

- cucumber

- red pepper

- carrots

- beets (which sweeten when roasted)

- orange or purple sweet potatoes

3. Start where you are.

If you’re eating 0 vegetables a day, try to get to 1 consistently.

If you’re eating 2 servings, shoot for 3.

If you already eat a sandwich for lunch, just add a tomato, some lettuce, or a couple slices of cucumber to it.

If you already make a morning Super Shake, throw a couple handfuls of spinach in there.

If you’re already making pasta sauce, add some extra peppers, mushrooms, or other veggies you enjoy.

You get the idea.

4. Explore, experiment, and discover what works for YOU.

Find YOUR path.

Be curious. Try stuff.

See what helps YOU eat more vegetables… and try to do more of that.

If you hate it and/or screw it up, who cares? At least you got out of your comfort zone, took a chance, and learned something.

But more likely, you’ll discover something else you enjoy.

SHARE