By Brian St. Pierre

How brain signaling drives what you eat. (And what to do about it).

It’s no secret that obesity rates have been rising in the U.S. (and other industrialized nations) for the past 30 years. It’s also no secret that Americans eat more than they used to; by almost 425 calories per day since the early ’80s.

For decades, government officials, research scientists, and fitness pros blamed this on a lack of willpower — folks’ inability to “push away from the table”. Diet book authors, TV doctors, and other nutrition experts tell us we’re gaining because of gluten. Fats. Fructose. Or whatever the nemesis of the day is.

But all this finger-wagging never really explains why.

Why are we eating so much food?

And why is it so hard to stop?

The answer lies in our brains.

You eat what your brain tells you to eat.

Ever open up a bag of chips planning to have a small snack, only to find yourself peering into an empty bag, just a few moments later?

Your brain is to blame.

Our rational, conscious brain thinks it’s in charge. “I eat what I want when I want it. And I stop when I want to”. But we have a lot less control than that. Behind our decision-making processes are physiological forces we’re never even aware of.

You see, deeper brain physiology drives what, when, and how much we eat — along with its co-pilots of hormones, fatty acids, amino acids, glucose, and body fat. For the most part, our conscious selves just come along for the ride.

In this article, we’ll explore:

- how our brains dictate so many of our food choices;

- how these physiological forces can lead to weight gain; and

- what we can do to take the power back.

Why do we decide to eat?

Simply put, we eat for two reasons.

- Homeostatic eating:

We eat to get the energy our body needs and to keep our biological system balanced (aka homeostasis).

- Hedonic eating:

We eat for pleasure (aka hedonism), or to manage our emotions.

Most meals are a mix of homeostatic and hedonic eating.

We do know that ghrelin, the “hunger hormone”, stimulates our appetite. It peaks just before meals, and falls during and immediately after eating.

Yet ghrelin is not the only factor in hunger or the decision to eat. For example, research shows that mice without ghrelin still eat regularly, just like the mice with ghrelin.

Although taking in nutrients is as old as biology, we still don’t know why and how humans get hungry and decide to start eating. Hunger and eating are shaped by many factors, including:

- our genes

- social cues

- learned behavior

- environmental factors

- circadian rhythm

- our hormones

As you can imagine, it’s complicated. So, science still doesn’t have “the secret” to hunger and eating. (Yet.)

We do, however, know a lot about why we stop eating.

Why do we stop eating?

Once we’ve started eating, what makes us stop?

This is in part influenced by satiation — the perception of fullness you get during a meal that causes you to stop eating.

(Satiety is sometimes used interchangeably with satiation, but the terms aren’t the same. Satiety is your perception of satisfaction, or reduced interest in food, between meals; satiation is your perception of fullness during a meal.)

When we eat a meal, two physiological factors work together to tell us to put down our fork and call it quits: gastric distension and hormonal satiation.

Gastric distension

When empty, your stomach can only hold about 50 mL. When you eat, the stomach can expand to hold 1000 mL (1 liter), or at the extreme end, 4000 mL (4 liters or 1 gallon).

Your stomach is designed to stretch and expand, aka gastric distension. Your stomach is also designed to tell your brain about how much stretching is happening.

As your stomach expands to accommodate the incoming food, neurons in your stomach send this message to your brain via the vagus nerve, which runs from your head to your abdomen.

At Precision Nutrition, we encourage people who want to lose fat to choose more nutritious yet low-energy and high-fiber foods, such as vegetables, beans, and legumes. Because these take up more stomach space, they can help us feel full, though we’re eating fewer calories.

Unfortunately, though, gastric distension isn’t the full picture.

Hormonal satiation

While you eat, your GI tract and related organs (like the pancreas) tell many areas of the brain that food is coming in. Some of these signals travel up the vagus nerve, while others enter the brain by different routes.

Some of the more important of these hormones are:

- Cholecystokinin (CCK): When we eat fat and protein, the gut releases CCK, telling your brain (through the vagus nerve) to stop eating.

- GLP-1 and amylin: Recent research indicates that GLP-1 may be the most unique, and important, satiation hormone. It seems to stimulate the production and release of insulin (a powerful satiation/satiety hormone itself) and slow down food moving from the stomach into the small intestine, among many other impressive mechanisms. Similarly, amylin is one of the few satiation/satiety hormones shown to actually reduce food intake.

- Insulin: When we eat carbs and protein, we release insulin. This tells your brain that nutrients are coming in, and eventually tells it to stop eating.

Many of these hormonal messages stick around. They can tell us to eat less at later meals, too.

(This is why you should think about your food choices and eating habits in the long-term — over the course of a day, a few days, or even a week. For instance, a high-protein breakfast might prevent you from overeating at dinner.)

Together, these physiological responses (along with other hormones and signals) help you feel full and know when to stop eating.

Yet these still aren’t the complete picture, either.

Your brain also drives your food consumption over time.

What really matters to your weight and overall health, of course, is what you do consistently — i.e. what and how much you typically eat, day after day.

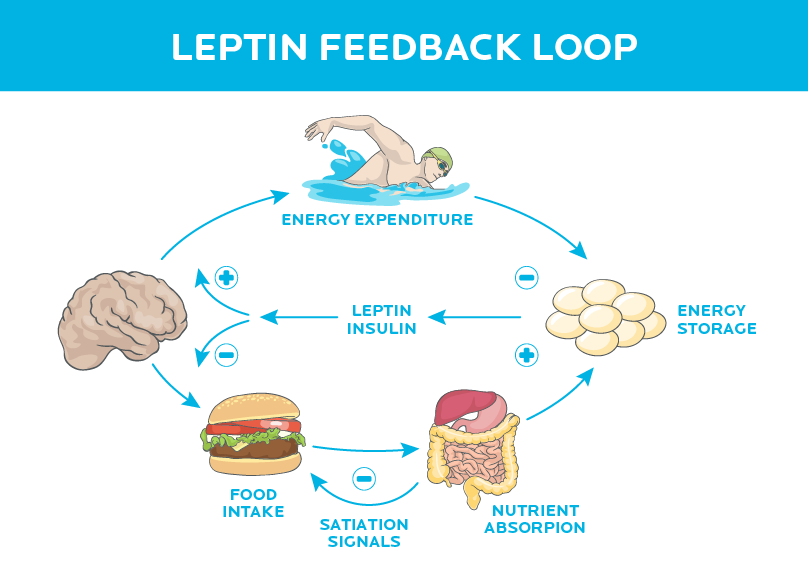

Your body has a system for managing your long-term energy and nutrient needs. It’s called the leptin feedback loop.

Leptin is a hormone that’s released by fat tissue. Leptin tells the brain how much energy we’ve just consumed and how much excess energy we have stored up (as fat). The more body fat we have, the more leptin in our blood.

The brain makes decisions based on leptin levels of hunger, calorie intake, nutrient absorption, and energy use and storage. Then, it cycles back to regulate leptin production in a loop that can help keep our energy (and body weight) balanced over time.

If stored energy (fat) and leptin remain stable over time, we are more easily sated during and between meals. Smaller portions feel OK. And our metabolic rate stays high.

If stored energy (fat) and leptin drop over time, it sends a message to the brain (mainly the hypothalamus, which links your nervous system with your endocrine system) that we need to start preventing starvation.

The brain responds to lower leptin levels with several anti-starvation strategies:

- We get hungry. Like real hungry. Like eat-your-own-arm hungry.

- We move around less. Our NEAT (non-exercise activity thermogenesis), or our daily movement like fidgeting, standing up, and anything other than purposeful exercise, goes down. The couch starts looking better and better.

- We burn fewer calories through movement as our skeletal muscles become more efficient.

- Our metabolic rate slows down significantly (as seen in the infamous ”Biggest Loser” study).

It follows, then, that if stored energy (fat) and leptin go up over time, you’ll want to eat less… right?

Yes. Sort of.

Unfortunately, you can’t always count on that response.

How much leptin will go up when you start eating more varies from person to person. And how your brain responds to increased leptin levels also varies from person to person.

Clearly, people’s physiologies vary a lot. In some people, when leptin rises, their brain decreases their appetite and increases their NEAT output. In others, the response isn’t nearly so robust.

That being said, most of the time, for most people:

The leptin feedback loop works well to naturally regulate our energy expenditure and consumption… until we disrupt it.

The food you eat can change your brain.

Assuming we’re properly nourished, that well-balanced leptin loop will tell us when we’ve had enough. It helps us feel sated and allows us to eat reasonable portions, comfortably.

But that nicely balanced loop can become disrupted — quickly — when we eat certain types of food.

A diet filled with hyper-palatable, hyper-rewarding, heavily processed foods can overthrow the brain’s “stop” signals.

In plain English, this means so-called “junk foods” that are sweet, salty, creamy, and/or crunchy (maybe all at once), and full of chemical goodness that spins our pleasure dials… but contain relatively few actual nutrients.

This type of diet prevents leptin from doing its job of regulating our energy balance. It can even make our brains inflamed and leptin resistant.

We end up feeling less satisfied. We want to eat more. And our bodies even fight to hold on to the weight we gain.

Hyper-palatability

Palatability is more than just taste — it’s our whole experience of pleasure from a food. That includes taste as well as aroma, mouthfeel, texture, and the whole experience of eating. Palatability strongly influences how much we eat at meals.

That seems obvious: Of course we eat more of the foods we like. And of course, some foods are more pleasurable to eat than others.

But some foods aren’t just palatable — they’re extremely palatable. They’re what you might call “too good”. Anything that you “just can’t stop eating” would fall into this category.

Reward value

Along with palatability, some foods give us a “hit” or a reward from some type of physiological effect. We’ll go out of our way to get foods with a high reward value — in fact, we may learn to like them even if they don’t taste very good.

For instance, few people like black coffee or beer the first time they try them. But coffee has caffeine (yeah!) and beer has alcohol (double yeah!). Our brains like caffeine and alcohol.

So we learn quickly that coffee and beer are good things, and we learn to like (or at least tolerate) their taste.

Over time we discover we like — maybe even can’t live without — them. We’ll wade through a crowded bar to buy a drink, we’ll stand in an absurdly long line for our afternoon coffee fix, and we’ll pay exorbitant amounts of money for relatively simple products.

We’ll also make room for high-reward foods even when we’re full. This is why at Thanksgiving, after moaning and groaning about how full you are, you miraculously make room for pie when it’s time for dessert.

Tasty + fun = no shutoff switch

Now, what happens when you put these two things — hyper-palatability (tasty) and high reward (fun) — together?

A dangerous combination.

We want these foods, we like these foods, and we’ll work hard to get them. When we do get them, we often don’t quit eating them.

These types of foods have a winning combination for keeping us interested and eating:

- energy density. i.e. a lot of calories in a small package

- high-fat content

- high refined starch and/or sugar content

- saltiness

- sweetness

- pleasing and specific texture, such as creamy or crunchy

- drugs, such as caffeine or alcohol

- other flavor enhancers or additives to improve mouthfeel

This magical mix is rarely found in nature. It is, however, often found in highly processed foods like cakes, cookies, pastries, pies, pizza, ice cream, fried foods, and so forth.

The more of those elements we have, the better.

Make something salty, and sweet, and starchy, and fatty, then add in some extra flavors and scents, appealing colors and a pleasing mouthfeel for good measure, and you have something that’s been scientifically engineered for us to over-eat.

We naturally love and seek out these things.

Evolution has equipped us for it.

If you love so-called “junk food”, and feel like you can’t stop eating it, you’re not alone, bad, or weird.

Your brain is doing its job to keep you alive.

For example, high-fat foods are energy dense. Good news if you’re a hunter-gatherer and nutrients are scarce. A sweet taste can tell us a food is safe to eat. Bitter-tasting foods could be poisonous.

Yet our ancestors weren’t exactly dialing in for delivery. They had to bust their butts with daily activity such as stalking, gathering, and digging, even for minor rewards like a meal of turtle and tubers.

Today, of course, high-fat foods aren’t nutrient-rich animal organs or blubber that we had to work nine hours to get; they’re Frappucinos and bacon double cheeseburgers that we bought while seated in our car.

Evolution’s gifts now work against us.

This is your brain on processed food.

Our brains loooooove processed foods. But our bodies don’t.

These enchanting and semi-addictive foods aren’t usually very nutritious. They have more energy than we need, with fewer nutrients (i.e. vitamins, minerals, phytonutrients, essential fatty acids, etc.) and fiber.

We don’t feel full or satisfied when we eat them.

After a while, our brain forgets about its natural “stop” signals in favor of getting more of that delicious “hit” from food reward. Our hedonic pleasure system starts bullying our homeostatic energy-balancing system.

Over time, if we eat a lot of these foods consistently, we might even injure and inflame the parts of our brain that regulate our food intake and energy output. Now our homeostatic regulation isn’t just getting pushed around, it’s also on fire.

We’re not sure exactly why this happens.

Getting too much energy from foods, and especially these foods seem to injure our brain’s neurons, particularly in the hypothalamus. When we are injured, we normally release inflammatory cytokines (aka cell signals). This happens in the brain as well (since the brain is part of our body), causing hypothalamic inflammation.

There is also evidence that significant consumption of these energy-dense foods changes the populations of the bacteria in our gut. Which affects the gut-to-brain pathway and also causes hypothalamic inflammation.

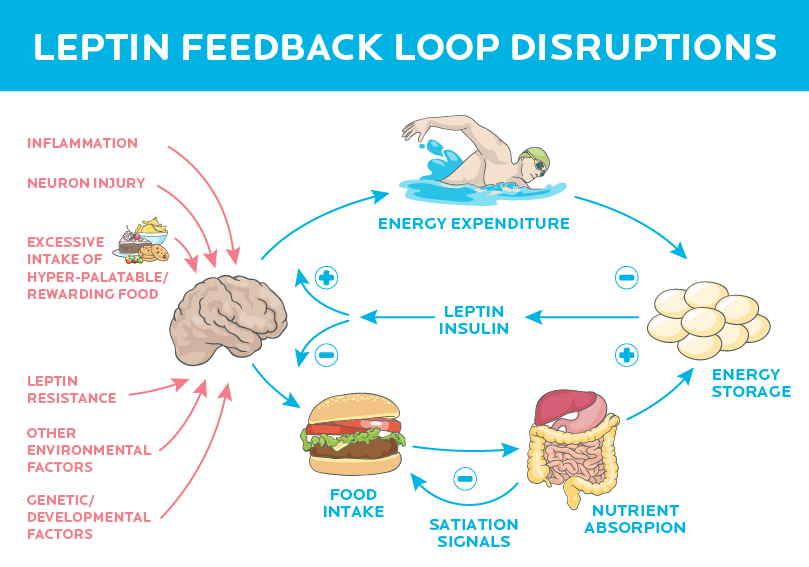

Hypothalamic inflammation then leads to leptin resistance.

Disrupting the leptin feedback loop

You might have heard of insulin resistance, the condition where people’s cells stop “hearing” insulin signals and slowly lose the ability to control their blood sugar levels.

The same thing can happen with leptin: Your brain can start to ignore or “tune out” the leptin, even if you’re eating enough, and have plenty of energy stored in your body fat.

In insulin resistance, the pancreas can simply pump out more insulin to keep blood sugar under control (at least for a while). Since body fat is our main leptin factory, to make more leptin, we need more body fat.

You see where this is going, right?

- When you’re leptin resistant, your brain thinks it doesn’t have enough leptin.

- The brain needs the leptin factory (i.e. body fat) to get bigger and produce more leptin.

- Operation Add Adiposity begins.

- You feel hungry. Regular portion sizes are no longer satisfying; it’s harder to feel satiated and you want to keep eating and eat more often.

- You gain fat. Mission accomplished, or so your brain thinks.

Here’s what the leptin feedback loop looks like now, in this disrupted scenario:

As if that weren’t enough, it seems this inflammation and resulting leptin resistance might even cause our bodies to defend our increased weight. (This seems to be because the brain now views this higher level of leptin and body fat as its new normal.)

In this case, our body fights even harder than normal to stop us losing fat. (Scientists are still researching exactly how and why our bodies do this.)

D’oh.

Hyper-palatable, highly rewarding foods are often the most readily available.

Tasty-fun food-crack deliciousness bombs are everywhere.

Today, these are the top 6 sources of calories in the U.S.:

- Grain-based desserts (cakes, cookies, donuts, pies, crisps, cobblers, and granola bars)

- Yeast bread

- Chicken and chicken mixed dishes (and we don’t mean chicken breasts — think chicken fingers, chicken stir-fry, and chicken nuggets)

- Soda, energy drinks, and sports drinks

- Pizza

- Alcoholic beverages

And:

- Fast food now makes up 11 percent of the average American’s energy intake.

- We now drink 350 percent more soft drinks than we did 50 years ago.

- Soybean oil (largely used in highly-processed foods) accounts for 8 percent of all calories that Americans consume.

All of this, of course, makes perfect sense.

If you’re a food company, you want people to eat your food.

How do you do that? Engineer the food to be extra-rewarding and hard to stop eating. People eat more, and buy more, and then lie awake at night thinking about how they could totally go for an ice cream sundae with sprinkles right now…

If you’re a savvy marketer, you might also invent new opportunities for people to eat.

Like… at movies. In the car. “Snack time” before, during, and after school. In front of the TV. At sports events. Before, during, and after workouts. Late at night (which is usually where processed foods excel). And so on.

Social norms and our environment also affect where, when, how, and how much we eat.

Now that food and food cues are everywhere, all the time, it’s hard to avoid wanting to eat, and hard to know when to stop eating.

Change what you eat, change your brain.

You can’t control your unique genetic makeup, your history of dieting, nor your physiological response. But you can control your behaviors.

Here are two simple (but not necessarily easy) steps you can take to help your natural appetite regulation system get back online and do its job better:

Step 1:

Eat more whole, fresh, minimally processed foods.

This means stuff like:

- Lean meat, poultry, fish, eggs, dairy and/or plant sources for your lean protein.

- Fruits and vegetables, ideally colorful ones.

- Slow-digesting, high-fiber starches such as whole grains, starchy tubers (e.g. potatoes, sweet potatoes, yams, cassava, etc.), beans and legumes.

- Nuts, seeds, avocados, coconut, fatty fish and seafood for your quality fats.

Step 2:

Eat slowly and mindfully.

No matter what you eat, slowing down will help your brain and gastrointestinal tract coordinate their activities. It will help you feel more in control of choosing what and how much to eat.

Plus, since the signals are getting through properly, you’ll often feel satisfied with less food.

Step 3:

Eat fewer processed, hyper-palatable foods.

Step 3 can be tricky. We get it. After all, this whole article is about how appealing those foods can be.

Step 1 and 2 will make Step 3 easier. If you get more of the “good stuff”, and stay mindful as you eat it, there’s often less room (and desire) for the other stuff.

Over time, if you do these 3 steps consistently:

- You’ll probably notice you crave highly processed foods less and feel more in charge of your food decisions in general.

- You’ll feel fuller for longer as that leptin loop returns to normal (at least to some degree, keeping in mind that each person’s body and situation is a bit different).

- You may lose body fat.

- You’ll probably find you feel, move and perform better, too.

++

Food intake is complex.

Physiology plays a big role. But so do psychology, relationships and our larger society, our culture, our lifestyle, our individual knowledge or beliefs about food and eating.

This means you aren’t “doomed” by physiology. You can use other things to help your body do its job.

A meal of whole foods, properly cooked and seasoned, and enjoyed at the dinner table with your family or friends is going to be much more satisfying than eating in your car next to the drive-through window.

You don’t have to live in a world of bland and depressing “health food” just because you aren’t carpet-bombing your taste buds. Throw a little butter and salt on those veggies. Make them taste good — just not “too good”, too often.

Your brain will love you for it.

What to do next:

Some tips from Precision Nutrition

Here are a few of our favorite strategies to help you find the right balance, and make smart choices.

1. Recognize that your body is a system. Think long-term.

What you do today can affect what happens tomorrow. Your breakfast can change your dinner.

If you restrict food and nutrients with a fad diet that “starts on Monday”, you might find your body aggressively taking back its energy by Friday.

2. Eat mostly whole, minimally processed foods.

Whole, minimally processed foods are not hyper-rewarding or hyper-palatable. It’s harder to over-eat them. They don’t cause hypothalamic inflammation and leptin resistance.

They have lots of good stuff (vitamins, minerals, water, fiber, phytonutrients, disease-fighting chemicals, etc.) and are usually lower in calories.

Here are some ideas for putting together a delicious plate.

Choose whole foods that you enjoy and will eat consistently.

3. Eat enough lean protein.

Protein is a satiety superstar.

We’ve seen in both research and our clients: When people eat more lean protein, they eat fewer calories overall. But they feel more satisfied. Sometimes even like they’re eating “too much”!

For most men, this generally means consuming 6-8 palm-sized portions of protein daily.

And for most women, this generally means consuming 4-6 palm-sized portionsof protein daily.

4. Eat plenty of vegetables.

Vegetables — especially colorful ones — are obviously super healthy. They give you a lot of volume and nutrients for very little calories. And many of them are fun to eat (think crunchy carrots, baby tomatoes, etc.).

For most men, this generally means consuming 6-8 fist-sized portions of vegetables daily. For most women, this generally means consuming 4-6 fist-sized portions of vegetables daily.

5. Get quality carbs and healthy fats from whole, less processed foods.

For carbohydrates, look for whole grains, beans and legumes, starchy tubers (such as potatoes and sweet potatoes) and fruit. The combination of resistant starch, fiber and water content will help you feel fuller, for longer.

When it comes to carbohydrates, for most men we recommend 6-8 cupped handfuls of carbohydrates daily. And for most women we recommend 4-6 cupped handfuls of carbohydrates daily.

For fat-dense foods, look to high-quality oils and butter, nut butter, nuts/seeds, avocados, and even a little dark chocolate. Fat tends to be digested the most slowly of all the macronutrients, especially sources that are less energy-dense and higher in fiber (e.g. nuts, seeds, avocados).

For most men, we recommend 6-8 thumb-sized portions of healthy fats per day. For most women, we recommend 4-6 thumb-sized portions of healthy fats per day.

6. Consider how you eat.

Work on eating slowly. Pay attention to your own internal satiety cues. Eat without your smartphone, TV, or computer in your face.

Eat from smaller plates. Create an environment in your home and workspace that makes it difficult to overeat or be tempted with highly-processed, highly-rewarding foods.

Remember Berardi‘s First Law: If a food is in your house or possession, either you, someone you love, or someone you marginally tolerate will eventually eat it.

This also leads to the corollary of Berardi’s First Law: If a healthy food is in your house or possession, either you, someone you love, or someone you marginally tolerate will eventually eat it.

7. Be flexible.

Recognize that it’s OK to have some of those highly-rewarding foods. Completely avoiding them, or demonizing them as “bad” or “poison” usually does the opposite of what you want: You feel like a guilty failure, and you often end up overeating or bingeing on those “banned” foods.

Instead, choose (in other words, decide in advance) to indulge in some occasional cookies, brownies or ice cream. Eat them slowly and mindfully, until you’re satisfied. Enjoy them.

And then move on, back to your regular routine like it ain’t no thing.

Keep in mind that how often you choose to indulge should depend on what you’re looking to achieve.

8. Be aware

Cultivate an awareness of how you feel before, during and after your meals.

Do you eat because you’re truly hungry, or because the clock says it’s time to eat, or because you just “feel snacky”?

Do you feel overstuffed at the end of a meal, only to find yourself staring into the fridge two hours later?

Where do most of your meals come from?

Consider keeping a food journal for a couple of weeks, making note of what you eat and how you feel. You can also jot down stuff like what you’re thinking, and what else is going on in your life (e.g. stress at work).

Simply becoming more aware of your body’s cues — and how these relate to other factors — will help you better regulate your food intake. Awareness helps you make decisions that are more in line with your body’s actual needs.